The automobile is an unusual object, one that imposes its own crazy infrastructure on the world, as well as shaping the landscape and the atmosphere just as much as our imaginations: an object found in the blind spot of our day-to-day lives. More than 1.2 billion automobiles are on the roads around the world today.

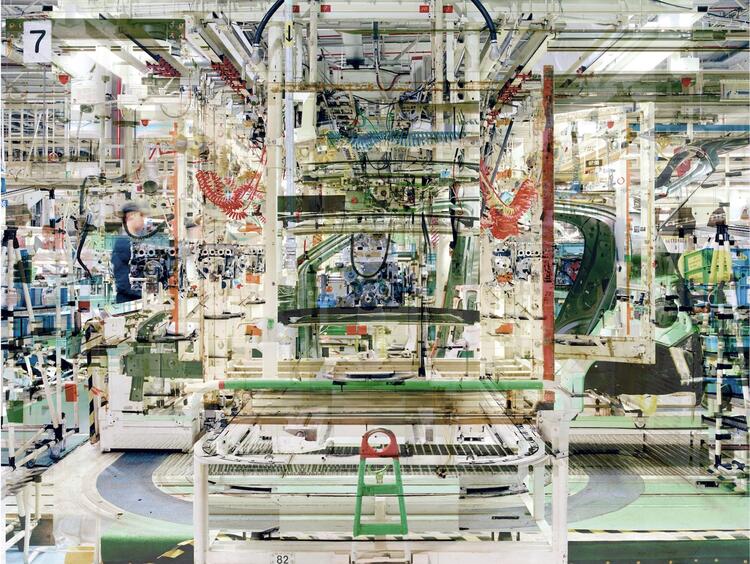

The automobile is much more than a collection of thousands of different parts: as its automation continues, it is becoming more like a digital device every day, devouring data, recording and describing our environment. Its appetite keeps getting bigger, needed more and more minerals and fossils to be manufactured: natural resources are finding it harder and harder to cope with its development

Autofiction presents a subjective, slightly embarrassing and often taboo biography of this object that now more than ever before is responsible for creating artificial, systemic, enormous and all-encompassing environments. Autofiction tells the story of the controversies rumbling away among designers and creators, thanks to three complementary biographical strands.

Part one is dedicated to the automobile as a four-wheeled smart electronic device. An automated, signal-receiving digital object, the car produces a description of our environments and of ourselves that consolidates its quality as a connected object, a system object, like the 1970s projects by the Ant Farm group, such as the Media Van that captured recordings from the areas that it travelled through and the individuals it met, before reproducing them inside the same van on California’s university campuses. More recently, through the inquisitive eyes of Olivier Bosson and Nicolas Gourault in films about the setbacks faced by self-driving cars, light has been shed on how fragile automated systems can be. While Benedikt Gross and Joey Lee’s vehicle-as-a-device lets us “see things like AI” to understand technology from the inside, Degoutin & Wagon’s robots take us back to our status as mobile animals.

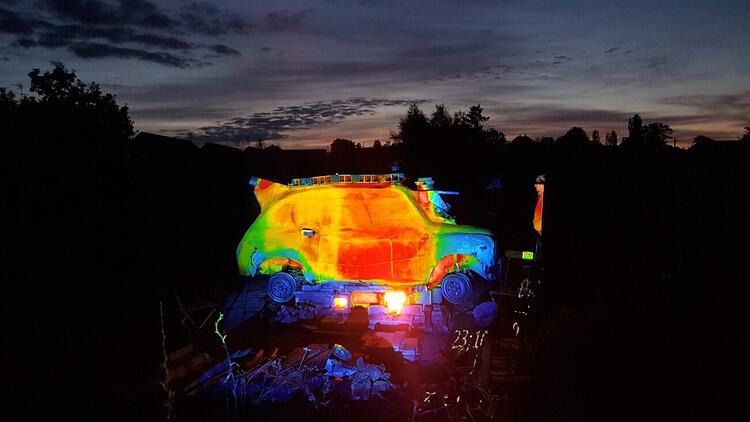

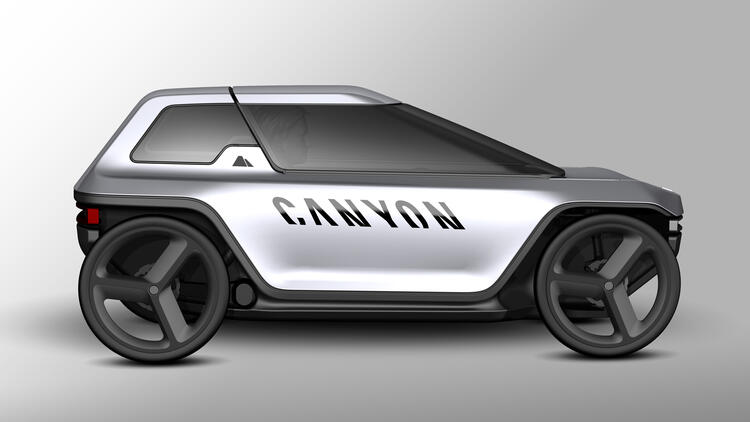

Part two features a short fossilised biography of the automobile, before opening up to the broader theme of today’s energy strategies. Electric solutions are not the only option that industry has: we can reduce size and consumption as the electric Microlino has done, make vehicles lighter like Kilow’s La Bagnole, focus on metabolism as the energy source for pedal-powered vehicles combined with electrical assistance as Midipile manages to do, or retrofit cars, playing with the rich heritage of the automobile, as demonstrated by Pierre Gonalons’ R5 Diamant for Renault: the possibilities are endless. For his part, Belgian artist Eric Van Hove draws on the savoir-faire of Moroccan craftsmen to remind us that car manufacturing started out as a craft, and could return to being one.

The final part opens up new narratives for the automobile. These stories come from artists and designers, who have come from Wolfsburg in Germany after the diesel gate crisis; from Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where the industry of finding rare metals for electric vehicles is having devastating consequences on local populations; from Cuba, where technological disobedience is facilitating a fragile form of survival; or from France, where ceramicists are drawing on the automobile’s past as a new resource. By sharing these imaginative new technical ideas, dreamt up by amateurs, we encourage a broad audience to explore what could be a technical democracy, thus reviving the notion of the automobile as a popular object.